By Brayden Wilson, SSC

Pain is an inevitable part of life, whether you train or not. You’ve decided to train in order to become more resilient and experience less pain day to day. However, maybe you have started to experience some pain from your training. What’s the deal? And what do you do about it?

Taking time off from training is NOT the answer. When dealing with minor injuries, there is always a tolerable entry point back into training and a path back to baseline. Continuing to train around your discomfort will allow you to hold onto the strength and skill you have worked so hard to acquire.

Total rest can often make pain worse and leaves you less tolerant to training when you return. Remaining consistent is another key reason to avoid taking time off; for most people, their first break from the gym after consistent training easily leads to the general habit of having a spotty gym routine.

It is much easier to stay consistent and adjust your training than it is to fall off and climb back on the wagon every time life throws a curveball your way. Now, onto some actionable steps to take in the gym.

A common reason for aches and pains for people who lift is improper load management; essentially, the stress of your program is more than your body is prepared for and can recover from.

This is typically the result of adding too much weight to the bar or too much volume to a lifting program too quickly. This is especially bad after being sedentary for too long. Temporarily reducing the overall stress of your program can help you manage your training while you are experiencing pain.

Even if you cannot do what you planned to do, there is something that you CAN do. The goal is to find a mode and intensity of training that results in either improved or stable symptoms over the next 24-48 hours.

If your symptoms worsen over the next 24-48 hours, the stress of your workout was likely too high for what the sensitive area can currently tolerate. Training variables we can adjust include load, volume, exercise selection, frequency, range of motion of a given movement, and tempo/speed of a given movement.

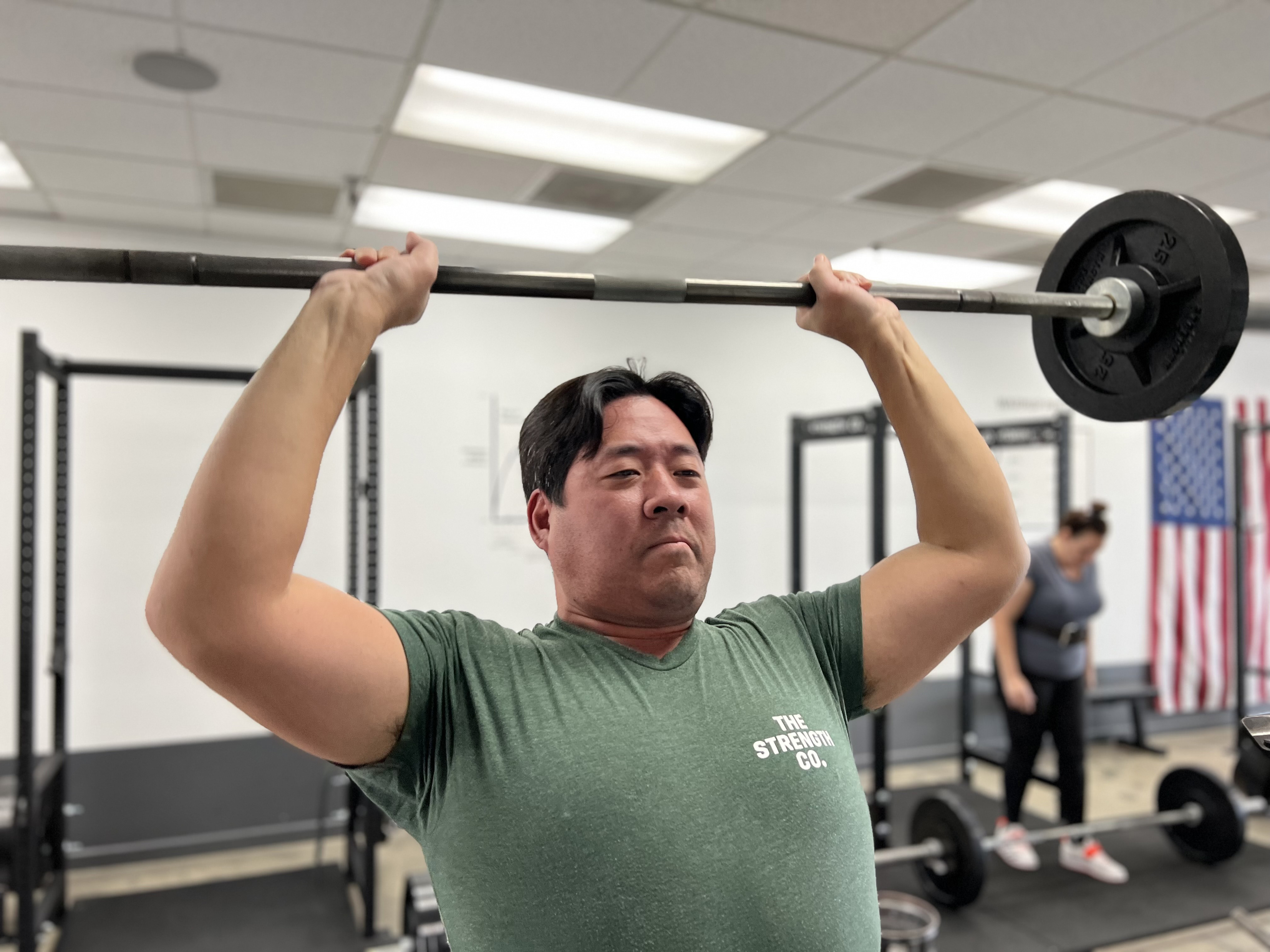

The best first step is often the most successful: reduce the weight on the bar. Say you are on the Starting Strength Novice Linear Progression, like you would be as a new lifter at The Strength Co.

If you planned to squat 200 pounds for the day’s workout and have been experiencing back pain during the past few workouts, it may be wise to select a lighter load that does not aggravate the sensitive area and gives it the opportunity to recover. You can still train and have a productive session without making your pains worse.

Ideally, symptoms will either improve or remain steady in the following 24-48 hours. This process may need to be repeated for several workouts until you are back to baseline. Some will have qualms with taking weight off of the bar when trying to heal up.

This is understandable, you’ve worked hard to get as strong as you have and do not want it to slip away. Rest assured, the gains will not slip away if you allow yourself to embrace the process, so do not let this be you.

Volume, the number of sets and reps performed for a given exercise, can also be adjusted downwards if you find that a certain threshold causes symptoms to worsen. However, if load is reduced adequately, the planned volume for the exercise should be able to be completed. It may also be helpful to increase volume while lowering the total weight to build a greater tolerance to the movement.

Frequency, how often in a week a lift is performed, also plays a role. It may be beneficial to be exposed to a lift more or less often, or have the same relative amount of volume spread over more or less time.

Exercise selection is another major variable that we can adjust during the rehab process. If deadlifts are aggravating, selecting a variation of the deadlift such as Rack pulls, Romanian deadlifts, etc. may be helpful. If bench press is aggravating a shoulder, it may be wise to perform a close grip bench press, or a pin bench press with a limited range of motion.

Variations of the main lifts have the benefits of being self-limiting in load and/or altering a range of motion that is not currently tolerable. If one of the main lifts is not tolerable, that does not mean that exercise is dangerous or will always lead to more pain. It simply means you are particularly sensitive to that movement at the moment.

Adjusting tempo, or the voluntary speed of the movement, can help reduce the “noise” in the system when trying to work a sensitive area. If the bottom position of a squat or bench press is painful, a three-second-long descent and/or ascent may be less painful. This also has the benefit forcing you to reduce load, due to the nature of the movement; you can not lift as much weight when intentionally moving it slowly.

If a certain position is painful, range of motion can be adjusted in order to still perform the movement more tolerably. If the bottom position of a squat or bench press is not tolerable, safety pins can be set to prevent the bar from accessing that painful range of motion. If pulling from the floor hurts, using rack pulls to abbreviate the range of motion is a viable alternative, with the goal to gradually reach the full range of motion over time.

It is important to note that nowhere in this article is “check your technique” listed as one of the steps to take. This is because inefficient technique does not tend to cause pain or injury, despite popular belief. As coaches, we coach and correct your technique because the more efficient it is, the more weight you will be able to lift. It is not to prevent you from injuring yourself, because that is generally not how most injuries occur.

The best way we as coaches can keep you injury free is to ensure you are not doing too much too quickly in the gym, and to match your programming to your current performance capabilities.

Your mindset regarding your pain and the road back to baseline is as important as any other practical recommendation in this article. Rehabbing an injury can be a frustrating process, and your recovery will likely not be linear.

Symptoms will ebb and flow, so maintaining a positive mindset about the process is key for getting yourself healed up. The natural course of injuries is heal over time if you do not actively make them worse. Find your entry point and adjust from there. You WILL get back to baseline, and ultimately surpass where you were!